Why Affordability and the Vibecession Are Real Economic Problems

There are many ways inflation makes people worse off even when real incomes recover, especially for essentials.

Affordability is a major concern among voters in practice. But is it a major concern in theory?

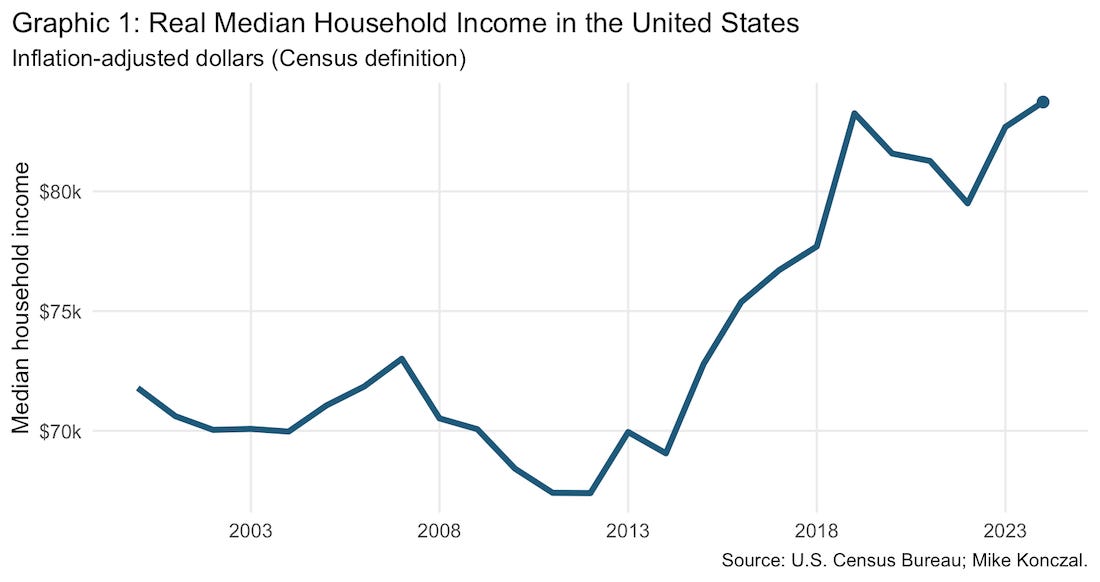

You’ve probably seen some version of Graphic 1 below, which shows real median household income from Census. After falling during the post-pandemic inflation surge, real incomes recovered. By 2024–2025, they had ended up higher than in 2019. This result holds across multiple ways of looking at this data, including hourly wage data. Yet consumer sentiment is stuck near historic lows, about as pessimistic as during the financial crisis and the depths of the Great Recession.

These two facts coexist. And the politics of “affordability” has rushed into the gap between them, as politicians and advocates try to speak to people’s persistent anxiety about prices and living costs.

But there has also been a subtle, yet real, pushback against this focus. That pushback usually starts from the observation that today’s affordability debate is inseparable from the 2021–2024 inflation episode. From there, two critiques follow.

The first is a money-illusion story: people fail to recognize that their incomes rose alongside prices, so their distress reflects confusion rather than material harm. This argument often emphasizes that incomes at the bottom of the distribution rose faster than those at the top, producing a durable wage compression. And yet polling consistently finds that lower-income households report more dissatisfaction with inflation, not less.

The second critique follows naturally. If what people really want is their old price level back, that is simply not something policymakers can deliver. Broad-based price declines tend to occur only in deep recessions, and even then only modestly. So it is said to be dangerous politics and bad economics to make affordability central. Doing so risks promising something impossible, or worse, flirting with economic collapse as a policy goal. Matthew Yglesias has made a version of this argument, affordability is “just high nominal wages” and “basically just anger at inflation,” as have others.

This conversation echoes what you often hear about the so-called “vibecession.” The term was originally coined by the writer Kyla Scanlon in 2022 in a nuanced way, to describe self-reinforcing pessimism. Today, it’s more often weaponized to imply that consumer sentiment is untethered from material reality, a reflection of the circulating bad vibes.

One could correctly say that these affordability problems existed in 2019 and are independent of the inflation wave. But we should take the bait. Over the past five years I’ve been haunted and utterly consumed by a keen observer of the debates over inflation. And I think it’s worth being explicit about why a wave of inflation can generate real affordability problems.

These mechanisms point toward specific policy interventions, many of which have already bubbled up in political campaigns. And they also help explain why President Trump’s current policy agenda is depressing sentiment, by placing pressure precisely on these channels. There are several, but the first is what matters the most.

1. The Essentials Squeeze

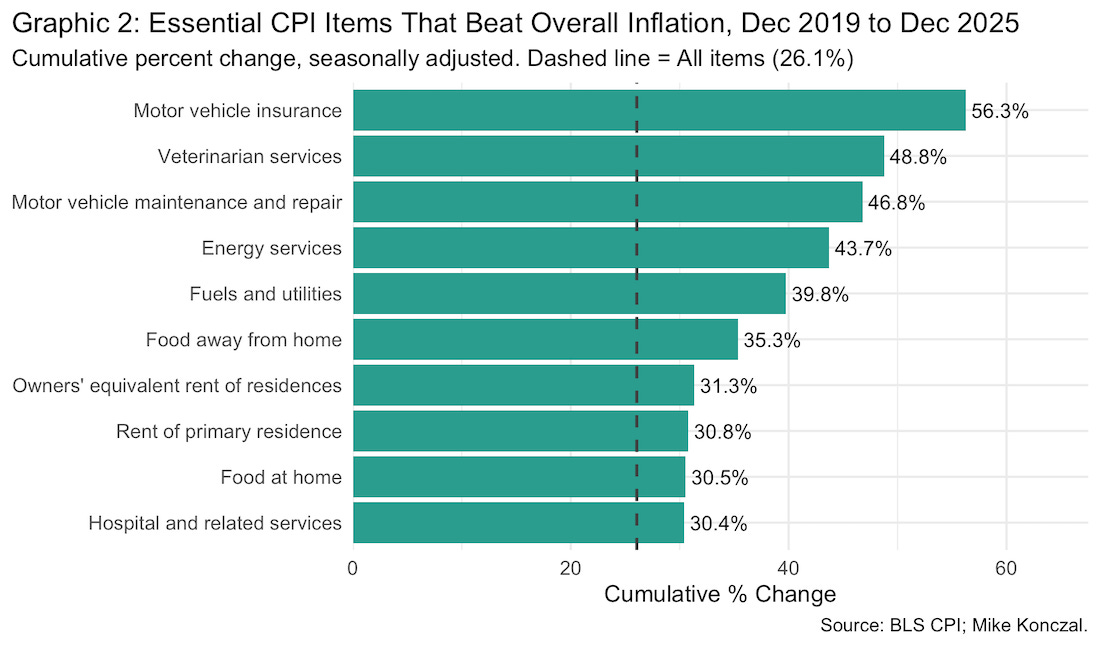

The simplest story is that essentials have been squeezed: their prices have risen faster than overall inflation, even as households are forced to devote more of their budgets to them.

Consumer prices have increased 26.1 percent over the past six years. But not all price increases are alike. Graphic 2 has some prices that have increased faster than overall prices during that time, ones that are pretty important for people. Food, shelter, transportation, hospitals, and veterinarian services all pop out. They’ve increased faster than both overall prices as well as core services (which rose 27.8 percent during this period).

Last week we discussed DoorDash. From Graphic 2 above, we can see that the price of food away from home (which includes delivery services like DoorDash) increased faster than groceries (food at home), and people shifted their spending to groceries. Given that spending on groceries tends to decline with income, we can understand this shift as a penalty people experience. Even if incomes stay the same, vibes (i.e. utility) decline.

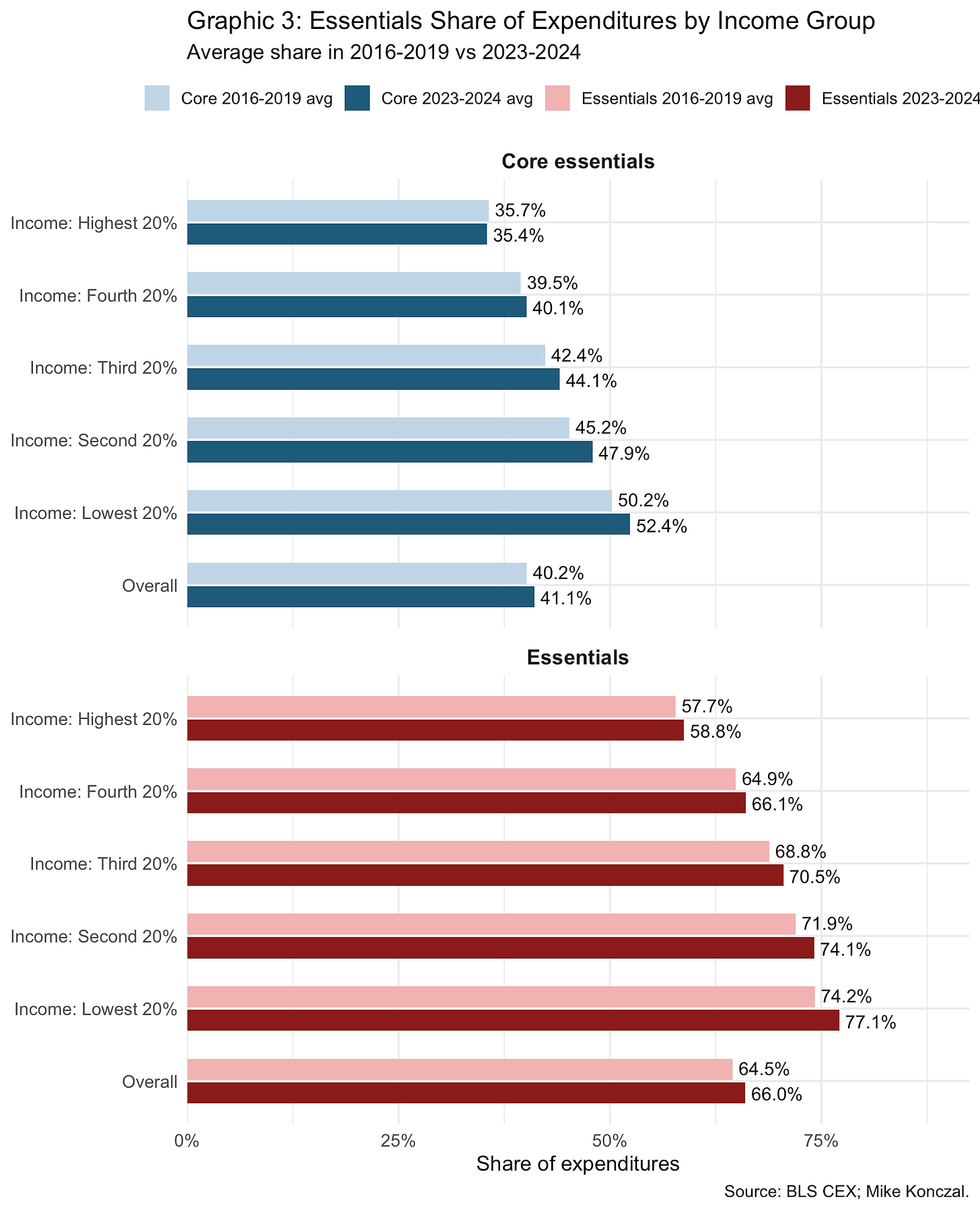

Let’s create two definitions of essentials. Core essentials are groceries and shelter. Essentials are groceries, shelter, healthcare and transportation. Taking the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) data, we can see in Graphic 3 that most households are devoting a larger share of their budgets to these essentials than they did before the pandemic, especially at lower incomes.

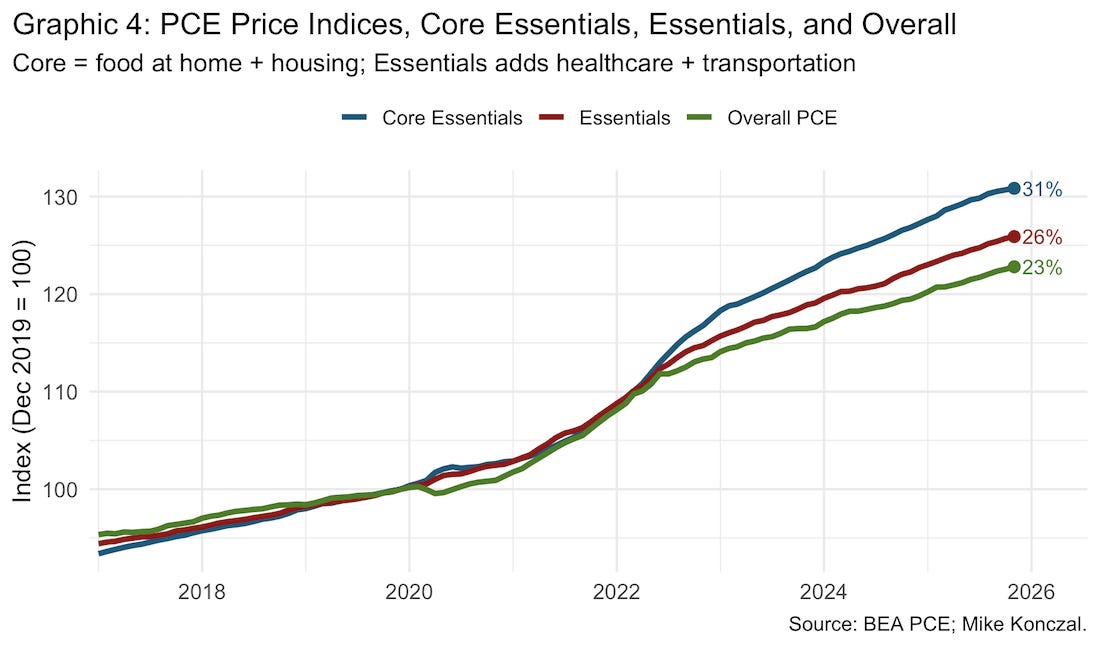

Is that because these goods are getting cheaper? No. Using PCE data, we can construct price indices for these bundles, weighted by their consumption shares.1 As Graphic 4 shows, both measures of essentials inflation have run well above overall PCE inflation.

The green line is overall PCE inflation, the blue line is an inflation index of groceries and shelter, and the red is the blue plus healthcare and transportation, all indexed by their consumption weight. As you can see, and as hinted from the CPI data in Graphic 2, the essentials are running much faster than overall inflation. This was true before as well. From end of 2013 to 2019, core essentials rose about 14.3%, essentials rose about 10.5%, and overall PCE rose about 7.9%. But this was supercharged in the recent period.

When prices rise and budget shares still increase, standard demand theory tells us these goods are necessities. If utility comes from consumption above some baseline floor, then a rising share devoted to essentials leaves less room for discretionary consumption and lowers welfare, even if total income keeps pace with total prices.

This also helps explain why lower-income workers are angry about inflation even as their wages rose faster than average. Households traded down to cheaper and generic food brands, a trend coined “cheapflation,” which drove up the prices for the basics that lower-income families depend on most. And as Catherine Rampell noted at the peak of inflation, CEX data show that lower-income households typically consume more than they earn and face more volatile work hours, both of which magnify the pain from price spikes.

The essentials squeeze alone is enough to provide microfoundations for the vibecession and affordability crisis. But it’s not the only channel. Let’s look at other ways inflation creates welfare losses that survive rational expectations. I’ll sketch them briefly.

2. The Housing Tilt Problem

This one is big in the older literature but is oddly absent from today’s debate.

As Modigliani and Lessard (1975) showed, standard fixed-payment mortgages interact badly with inflation even when inflation is perfectly anticipated.2 Higher inflation raises nominal mortgage rates, preserving real interest rates. But because mortgage payments are fixed in nominal terms, higher nominal rates mean much higher initial real payments that then fall rapidly over time. Real payments are front-loaded.

MacGee and Yao (2025) show, using modern life-cycle models, that when borrowing constraints bind at origination, this front-loading tightens credit for first-time buyers. People with steep expected income growth but limited current earnings must qualify against today’s higher nominal payment even though that payment will shrink quickly in real terms as wages rise.

If this is too complicated, it’s just another reason the housing market has been a mess.

3. Planning Under Uncertainty

Binetti, Nuzzi, and Stantcheva (2024) find from surveys that the most commonly cited consequence of inflation is not any specific price increase, but the complexity inflation introduces into everyday decision-making. Eighty-five percent of respondents identify this as a major effect, and more than a third rank it as the single most important one.

When prices are stable, budgeting is boring. When prices are volatile, households must constantly plan when to buy, what to delay, how much to save, and how to interpret nominal changes. That cognitive effort is costly.3

4. The Cost of Money Is Part of the Cost of Living

Another issue is that we largely exclude borrowing costs from how we talk about inflation.

As Bolhuis, Cramer, Schulz, and Summers (2024) show, incorporating borrowing costs into measures of consumer sentiment explains a lot of the U.S. sentiment gap. From a household perspective this is obvious. The interest payment on a new mortgage is several times higher. Interest on new car loans is up sharply. People, especially lower-income ones, experience this as part of the cost of living.

Official inflation measures abstract from interest costs for good monetary and economic reasons. But that creates a gap between measured inflation and lived affordability.

There are others, which we might discuss in the future, but this is a solid grounding.4

Conclusion

When the prices of necessities rise faster than everything else, when housing becomes mechanically harder to access, when planning gets more cognitively costly, and when borrowing is more expensive, welfare can fall even if average real incomes recover.

The good news is that these binding constraints are solvable problems. We have many ideas for tackling housing, healthcare, and food costs. Simple steps like not slapping century-high tariffs on foods like bananas on the fantasy that they create leverage, or not cutting a trillion dollars from Medicaid to cut Amazon’s corporate tax bill in half, would be a great start.

But the first step is to believe that what people have been screaming about their lives for the past several years actually exists. Even a representative agent, forward-looking and fully aware of all the parameters surrounding them, can feel the vibecession.

Code is here. I switch from CPI to PCE here because PCE makes it significantly easier to construct custom price indices, since category weights can be directly calculated as shares of nominal expenditure. With CPI, comparable weights must be manually assembled across a much longer time span. PCE does differ in how some categories are measured, especially with healthcare, and understates the impact of shelter due to its lower PCE weight. But, as Graphic 2 suggests, the story is the same under either index.

From their paper: “[I]nflation has an adverse effect on the demand for houses financed through mortgages, because the rise in the mortgage rate results in a distortion of the time pattern of real mortgage payments, that is, payments expressed in dollars of constant purchasing power. In a world with inflation, real mortgage payments are much higher in early years and much lower in later years […] To the extent that households are constrained in the amount of housing they can afford by the size of the monthly payment relative to their income in the first few years of the contract, this distortion will depress the demand for housing and result in financial hardship.”

I read this as different from traditional “shoe-leather” costs, though they are described as such. I do appreciate those kinds of cash-in-advance models more now. Having two kids and paying for two daycares during this inflation surge, you really do feel the cost of needing large amounts of non-interest-bearing liquidity in the presence of borrowing constraints. Kids are a cash, not credit, good, that trade off against leisure. In an economy like this, the decision to have a baby can break the superneutrality of money even under rational expectations.

This post is keeping with my promise last fall, while creating a baby Euler equation, that all my Substack takes will have microfoundations and survive rational expectations. But we should look at some others reasons for the vibecession that don’t, including stimulus withdrawal, and, something I’m noodling on, that people care more about absolute rather than percentage changes.

But staying with rational expectations, I’m adding this specific one here because I’m a little less sold on it but do want to include. It’s a brilliant model and I appreciate anyone doing the hard work of replacing New Keynesian price rigidities with wage ones. But my experience of the data is that workers really enjoyed the labor market of 2021-2022, they were just angry about the product markets. I also understand the data to show many took the moment to upgrade their jobs, not just moving laterally or fighting over various marginal costs, but getting footholds in higher wage, higher productivity occupations and industries, which is different than their dynamic. But including:

5. The Conflict Cost of Wages

Last, nominal wages did rise rapidly from 2021–2024. But getting those raises wasn’t frictionless. Much of it came from job switching. As Guerreiro, Hazell, Lian, and Patterson (2024) argue within a New Keynesian framework where wages have adjustment costs, workers dislike inflation in part because it forces them into the costly conflict of searching, switching jobs, negotiating, and asking for raises.

Even if real wages eventually recover, the process of getting there imposes time, stress, and risk on workers. That’s a welfare loss.

So you're converted to the cause of fiscal austerity and deficit reduction?

Nailed it: “But the first step is to believe that what people have been screaming about their lives for the past several years actually exists.” Differentiating core essentials is obviously critical for those in the bottom half of the K distribution but as a signifier, it’s important for a lot more of us who actually go to the store to buy stuff.