The Baby Euler Equation

How rational expectations model the fertility gap and clarify the debate over pronatalism.

It’s the holiday season, let’s do a fun post that won’t be for everyone. But if you make it to the end, you can see how proper economic microfoundations can clarify the debate over pronatalism on the left. Last week, we dug into the fertility data and started to build a take that worked in practice. But does it work in theory?

The take I’m exploring is that we should be thinking of the slowdown in fertility in terms of marginal penalties that would be best served by focusing on the concrete, near-term barriers facing people in their late 20s and early 30s. Others have written along these lines. Rachel Cohen Booth writes about how the “economy isn’t built for the biological clock.” Suzanne Kahn notes, in a recent book review of After the Spike by Spears and Geruso, that a goal should be “lowering the opportunity cost of children” especially “by giving parents more time.”

But does this take survive contact with rational expectations? We stress test all potential takes around here, including hitting them with the question of microfoundations. Our take must remain valid even when we assume people are forward-looking actors who will actively change their behavior to anticipate and react to changing constraints and policies. I don’t want to be doing my new take on a podcast or a panel, and suddenly get blindsided by the Lucas Critique.

This is extra relevant as we discussed issues with total fertility rate (TFR), which you can find more about from Our World in Data and The Conversation, a measure that assumes current timing stays fixed and people don’t shift births around.1 Put differently, TFR doesn’t survive rational expectations, it’s a statistic that can’t keep up with how real people optimize against changing constraints. But how well does a theory of penalties survive this test?

Model Setup

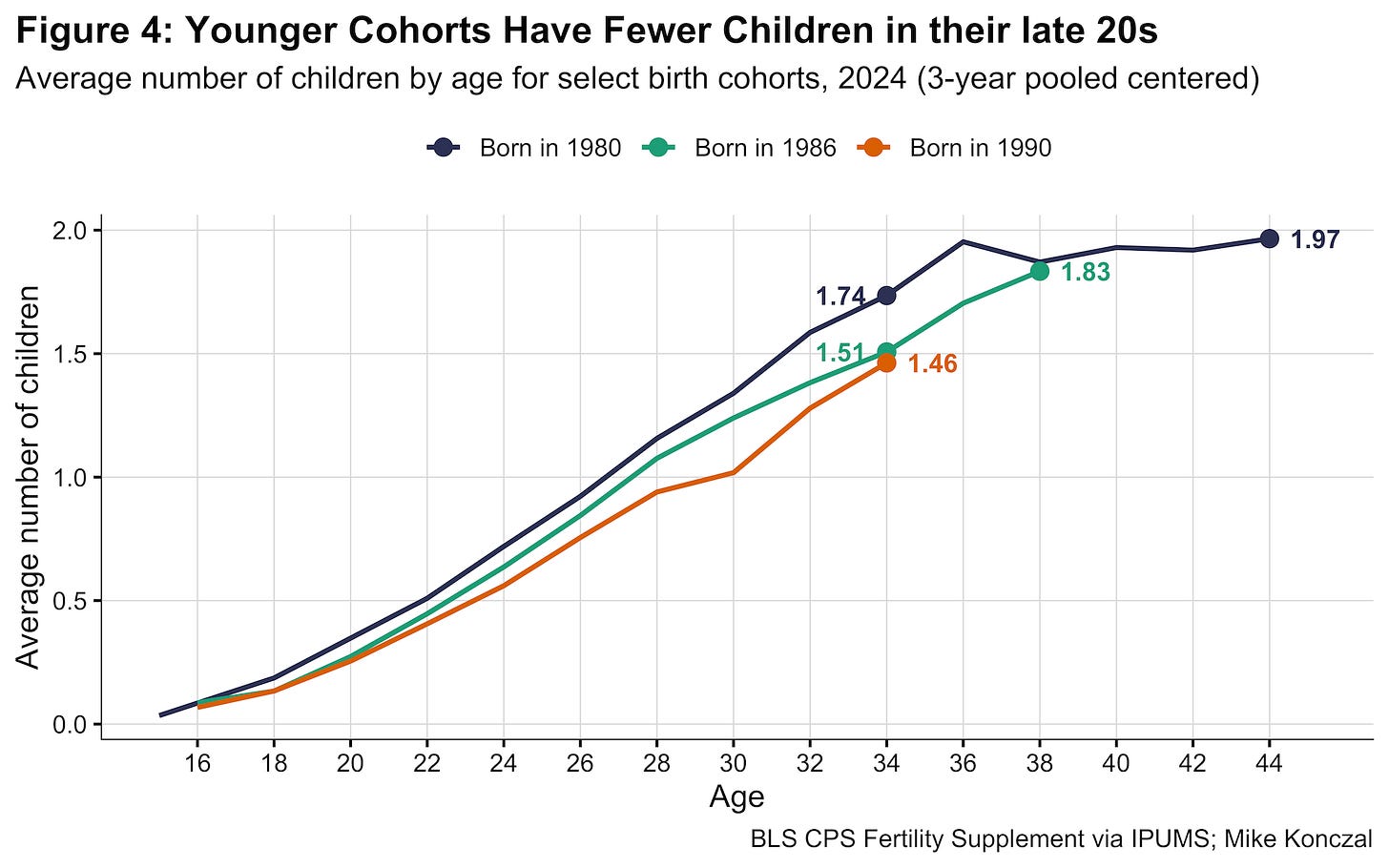

We also have this graphic from our dive last week:

Between the 1980 and 1986 cohorts, we see a notable slowdown in when people start families, even though they eventually arrive at the exact same destination. They both start with ~0 kids at age 15 and end up with 1.83 kids by age 38. But the 1986 cohort takes a very different path, delaying those births.

Whether or not it has forgotten how to answer basic questions about the business cycle, current macroeconomics excels at modeling how an ethereal representative agent allocates decisions across an infinite future under perfect information. Though young people would probably say, if not phrased exactly this way, “I don’t understand the parameters of how to date on apps and raise a family in this moment,” that isn’t going to stop us here.

There’s a literature around how future-looking agents decide to have children, built around models by Becker and Barro (not that one). Usually, those models are trying to solve complex problems like intergenerational wealth, cross-country comparisons, or human capital accumulation. I want to keep our model of a penalty very simple, a toy model we could build on later. What does our hypothetical “penalty” do?

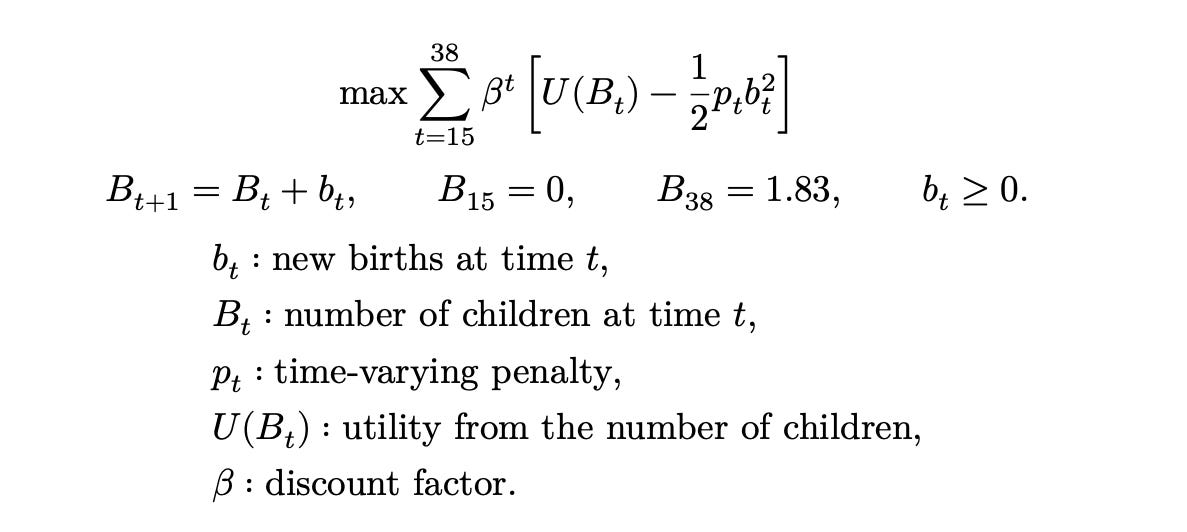

We imagine a representative agent for the yearly cohort, who can choose a fraction of a child each period. Today’s choice to have a kid, bₜ, adds to tomorrow’s number of kids, Bₜ₊₁. Now you love your children equally, of course. But your love, U(Bₜ), is twice-differentiable, with the first derivative strictly positive and <looking around to make sure the kids are out of earshot> the second derivative strictly negative. And, last, there’s a penalty, pₜ, to having a kid at time t, that can change over time. The penalty is quadratic, which means the more you have kids in a period, the more the penalty bites. The agent starts with no kids, knows all the things, and also knows at 38 they’ll have exactly 1.83 kids.

All pretty straightforward? Let’s write that out.

Baby Bellman

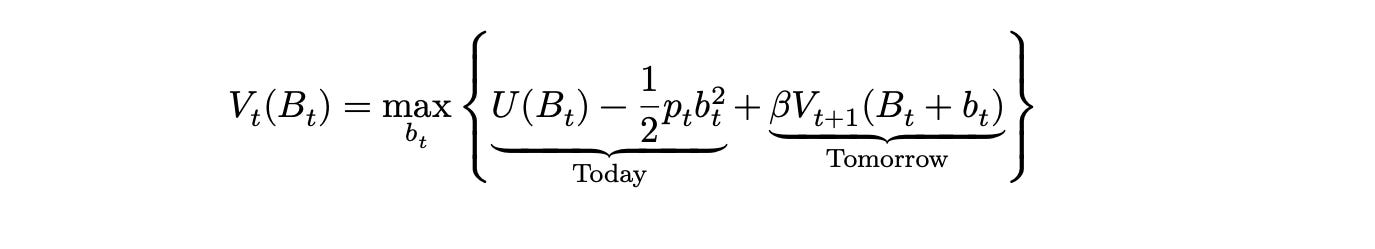

Now we can solve this baby equation with a baby Lagrangian or a baby Bellman equation. I want to use the baby Bellman equation.

I actually think this recursive structure is a great way to think about fertility. Don’t get lost in the equation. V(B) is the value of having kids to our agent. How does it model when to have kids? A decision today, that’s the left part, and a decision tomorrow, that’s the right part. But what’s the decision tomorrow? It’s also V(…)! It’s the same equation, the same decision, but just repeated tomorrow.

Many often think “when’s the right time to have kids?” In the Bellman world, there’s just two time periods: today, and tomorrow, and tomorrow is just today all over again. But a little more exhausted, as you have to discount. You can literally have infinite time but you’ll still just have two times: today, and tomorrow, which is just today’s decision repeated again. It’s today all the way down. (There’s no good time, just have the kids.)

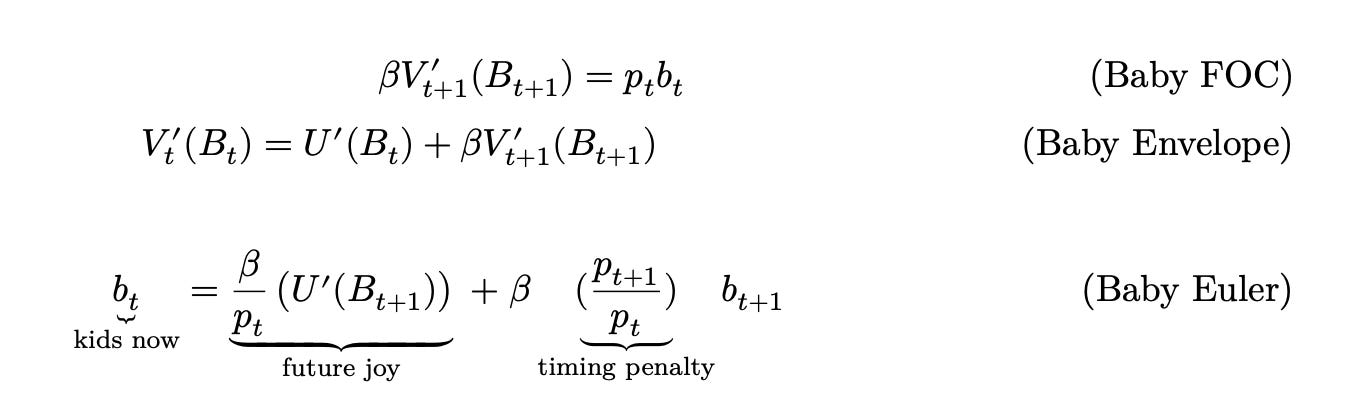

Baby Euler Equation

Yet people are shifting fertility around, and we have a way of determining how to assess that trade-off: the Euler equation. We take the baby Bellman equation, and take the baby first-order conditions. From there we apply the baby envelope theorem, which gives us the baby Euler equation:

Let’s focus on the Euler: The left side is b at time t, which is the decision to have a kid now. The thing that makes this unique is that b at time t+1 is on the right side of the equation; it is reflecting the decision today explicitly against the decision tomorrow. The logic is that you balance your decision-making so you are indifferent between moving just a fraction of having a kid between today and tomorrow.

Let’s talk about the term labeled “timing penalty,” which is the penalty tomorrow divided by the penalty today, that is added to the decision to have kids now. I’m going to assume you hate math and are mad you got here and take this slow, because it’s important. When the penalty today grows larger than the penalty tomorrow, the denominator gets bigger than the numerator; that number goes down. And you are adding it to b, the decision to have a kid, so it decreases having a kid now. If the penalty tomorrow gets larger than the penalty today, the opposite happens, the numerator grows faster and the number of kids today increases.

Or, in terms of life, when young women face higher penalties today, like unstable jobs, thin safety nets, career costs, expensive childcare, relative to what they expect tomorrow, they delay births. And when anticipating higher future penalties, like infertility or balancing aging parents, they shift births earlier.

Note if you don’t hate math you can just take the derivative of having a kid today with respect to the two penalties (noting p is positive and b is non-negative) and get the same result, a higher penalty today lowers today’s fertility and a higher penalty tomorrow increases it today:

With very simple assumptions, a rational agent will spread the timing to have children seeking out when the penalty is lowest. One can even try to estimate the penalty, which is an exercise for the footnotes.2 I believe my new take survives rational expectations, so I will continue to build on it.

Pronatalism Under Microfoundations

Currently there’s a lot of interest in “pronatalism,” though it’s often difficult to pin down the politics of it, especially on the left. But this is where microfoundations can clear the confusion, by examining the penalty in the baby Euler equation.

We can identify two different approaches to this equation. There are those who want to alleviate the penalty term, to reduce pₜ in those critical late-20s and early-30s years when the penalties are currently highest. This approach takes the equation seriously and asks what makes the denominator spike for young adults today, then works to address those constraints directly. Childcare, paid family leave, housing policy that builds, child allowances, healthcare, and workplace flexibility, all to move the marginal penalty. This path respects the optimization problem, acknowledging that people are rationally responding to real constraints, and seeks to lower those constraints so the penalty is smaller during these years.

Then there are those who want to suppress the ability to time, to remove b as a choice variable entirely. (Choice as in both the reproductive and Bellman sense.) This is happening with anti-choice campaigns to eliminate access to abortion and contraception. It’s also happening with the Trump administration broadly, most recently moving to reclassify nursing and other female-dominated fields as non-professional degrees, raising financial barriers to access. This is based on the conservative argument that preventing women from accessing higher education can increase fertility, one that, as Darby Saxbe shows, is wrong on its own arguments. You can’t make the timing choices that works for you if you have no control over your life or your economic future.

Both approaches seek to change fertility patterns, but through fundamentally different mechanisms. One lowers the barriers people face in having the families they want when they want them. The other removes the ability to choose, to time at all. One side trusts women to make decisions for themselves when constraints are eased. The other side sees women’s decision-making itself as the problem to be suppressed. If there’s a question of pronatalism in front of you, ask what side it’s on. And always ask yourself, what side are you on?

One of my favorite responses was Jeff Baker saying “Total Fertility Rate is one of those dangerous statistics that nobody understands. It is up there with ‘vacant homes per capita’ in terms of how often it is used in the discourse by people who do not know what it means.” Someone needs to make a 2x2 political grid on people who aggressively use vs show skepticism of both TFR and vacant homes per capita. Here’s Ned Resnikoff on why home vacancy numbers are a red herring.

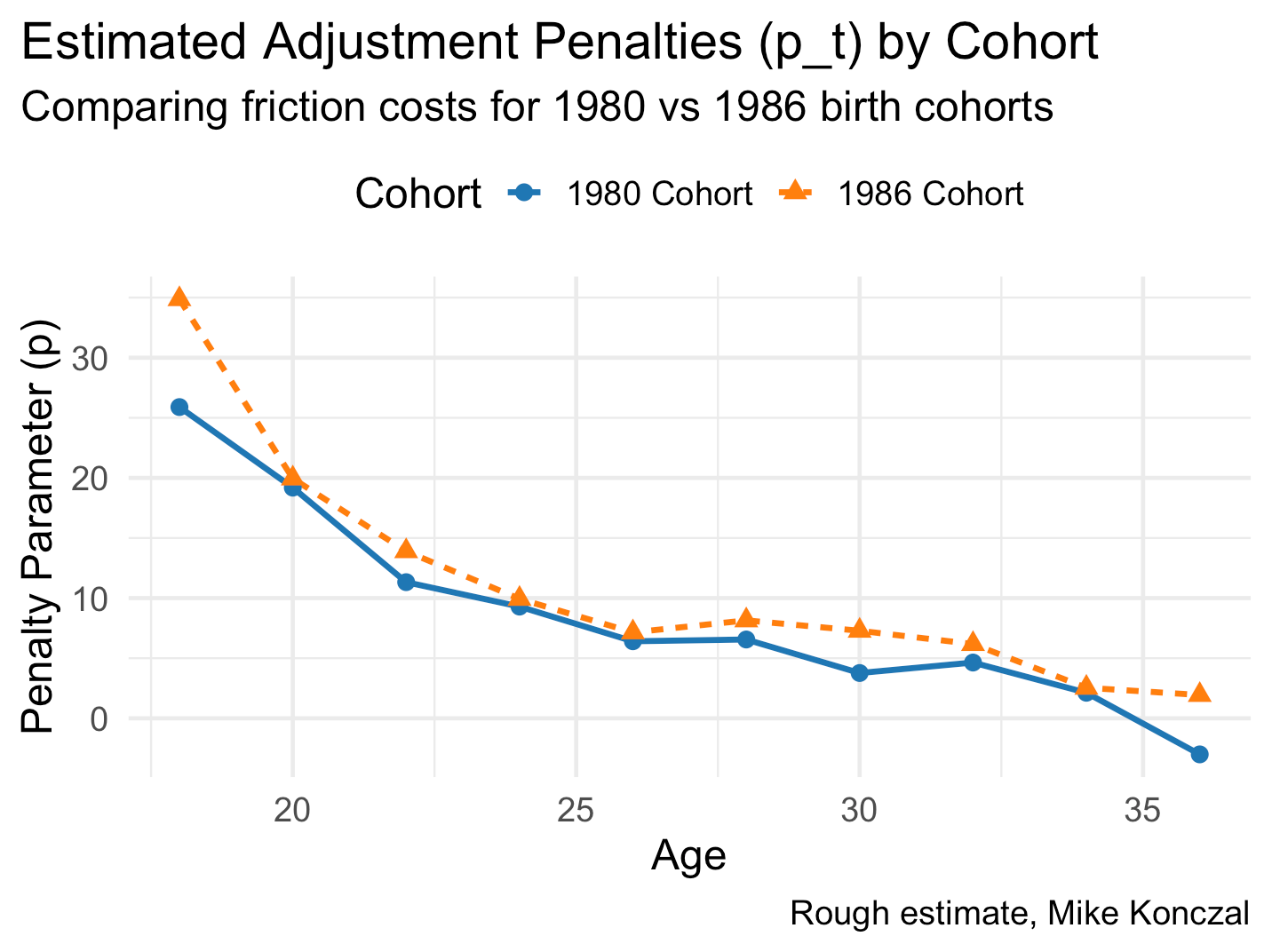

I’m going to pause here and say I am not confident that this next section is correct, and it may just get deleted. Dynamic macro numerical methods is not something I’ve allocated skill points toward. Outside the academy it seems to mostly allow you to work at the Fed, and there’s a small chance the Supreme Court is going to say that the new job of the central bank is to just do whatever random 24-year-olds in the West Wing tell them to do, just as the Founders intended. If any serious macro people want to read the code and give feedback I’d love it!

But we came this far. We have the recursive model, and we have two historical fertility paths that end up in the same place but with different timing. We don’t have anything random to keep it simple. Let’s take log utility and set β to 0.92 (it’s every two years for a period) and back out the implied penalty for each period. This isn’t really estimation, it’s just walking the implied penalty backwards.

I think this is correct, that this is the penalty sequence {pₜ} that creates the the birth pattern for birth year 1980 and 1986 for the model above. If so, notice that the penalty from 28 to 32 is higher for 1986. But note that this higher penalty is not that much higher. In fact, it’s as if it just doesn’t get easier at 30 than it was at 26. But many of those likely increased penalties (building more housing, above all) are addressable, if we want it.

Great take.

Can you apply this to South Korea? I read lately of a 0.52 TFR. Could this just be couples choosing over the last X years to delay their first child by Y years? What are some Xs and Ys that would make this true?