Stop Blaming DoorDash for the Affordability Crisis

One DoorDash Discourse to rule them all: Food away from home is down. Groceries are up. This is especially true for young people. Affordability is a real problem.

I was in the middle of a post providing microfoundations for the affordability crisis and the vibecession, showing how both can exist under rational expectations, when I decided to cleave off a portion of the analysis to engage in DoorDash Discourse. (We’ll get back to that within the week.)

Nothing gets the internet going quite like a round of hand-wringing about whether too many people, especially young ones, are spending too much money on delivery services, distorting their sense of budgeting and of how the economy actually works.

However, DoorDash Discourse is mostly wrong.

People are not, in aggregate, spending more on eating out and delivery. They are spending more on groceries at home and less on food away from home. This is especially true of young people.

The last round was kicked off over the weekend with “Freedom With a Side of Guilt: How Food Delivery Is Reshaping Mealtime” from Priya Krishna at the New York Times:

In 2024, almost three of every four restaurant orders were not eaten in a restaurant, according to data from the National Restaurant Association. The number of households using delivery had roughly doubled from 2019, just before the pandemic, the group said. And in a survey last year, about one-third of American adults told the association that they ordered food for delivery at least once a week. […]

That disconnect extends to restaurants, many of which have accepted a trade-off: Delivery helped keep them afloat during the pandemic and expanded their customer base, but they now have fewer in-house diners.

This predictably produced a wave of takes about personal irresponsibility and moral failure. A representative tweet comes from Matt Yglesias: “Part of the affordability crisis is pretty clearly people just refusing to be thrifty — you should not be spending a quarter of your salary on DoorDash.”

I have no doubt that food delivery has picked up and normalized since the pandemic. The relevant economic question, though, is not whether delivery exists. It’s what it is displacing. Is delivery mostly replacing groceries cooked at home? Or is it mostly replacing eating in restaurants?

Positive Analysis

We have a place to look. The Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey (BLS CEX) is a nationally representative annual survey of consumer units that reports annual spending by detailed category. It is the primary federal source for household expenditure patterns and is widely used to understand cost burdens, to inform CPI weights, and to benchmark how budgets shift over time. The CEX makes it possible to compare budget shares across time and across demographic groups such as income quintiles and age.

The latest data for 2024 came out in December 2025, delayed because of the government shutdown. This data can help explain why people’s experience of the economy has been poor even when aggregate income growth keeps pace with inflation. A rising share of budgets devoted to necessities will make households feel worse off.

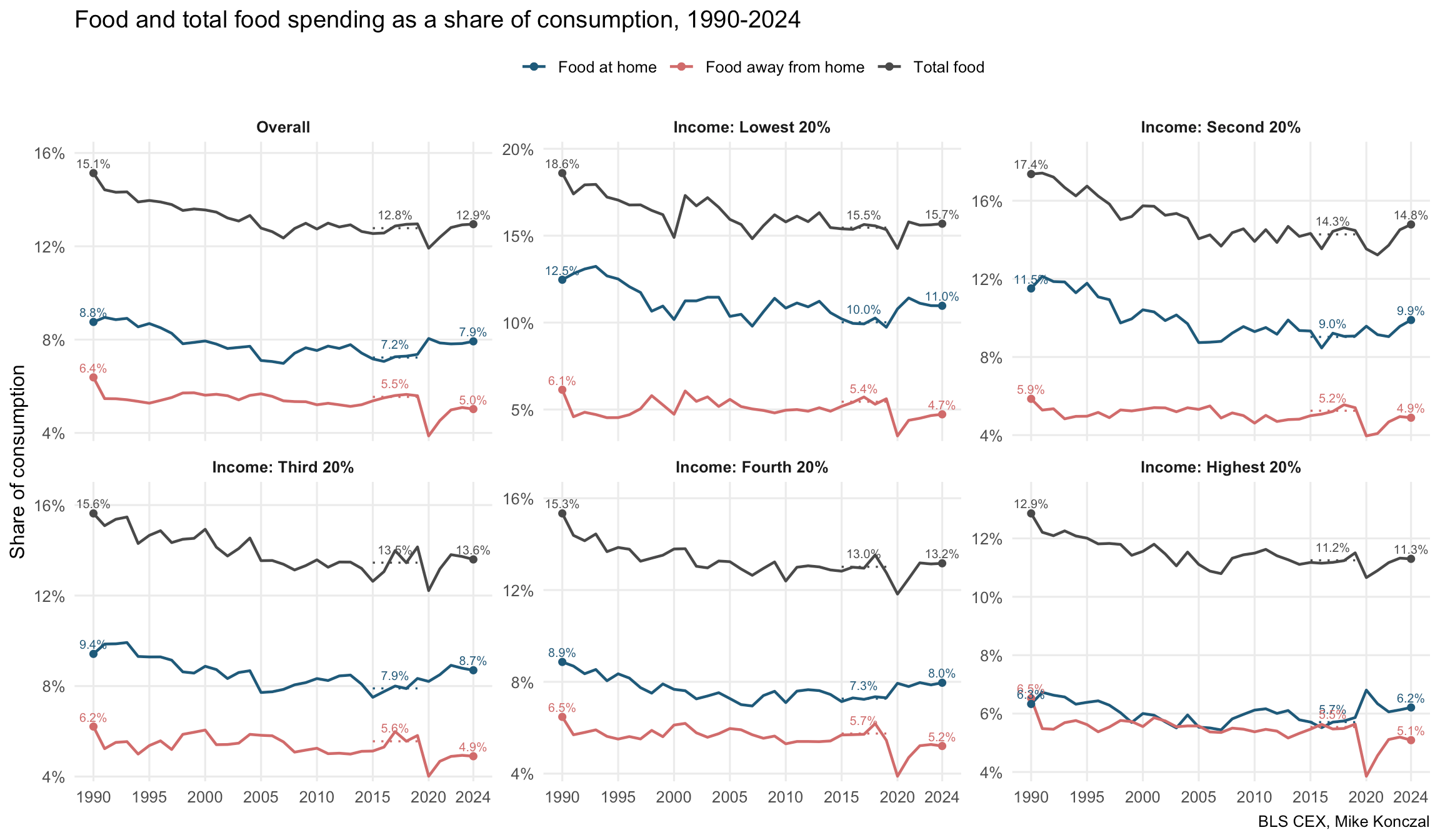

Here is “food at home” and “food away from home”1 as a percent of total consumption2, for all families and by income quintile.3

The dotted-line and middle number are the average for 2015-2019. Here’s those numbers in a simplified chart:

What do we have here? Start with the post-2019 period. Overall, Americans are spending about the same share of their total budgets on food. For the bottom 40 percent of households, the food share is modestly higher.

But compositionally, there has been a clear shift. Less of the food budget is going to food away from home (which includes delivery and takeout). And much more of the food budget is going to groceries.

In other words, society as a whole is reallocating food spending toward cooking at home, not away from it. DoorDash Discourse gets the direction wrong.

Normative Analysis

Is this shift necessarily bad? And does it support affordability as a real political and economic concern?

I think yes, for two reasons.

First, the shift is bigger for the bottom 40 percent of incomes. Lower-income households are doing much more of the adjustment toward food at home than higher-income households. This is not just a uniform cultural pivot toward staring at your phone rather than going to a restaurant. It is a stratified adjustment likely driven by constraint.

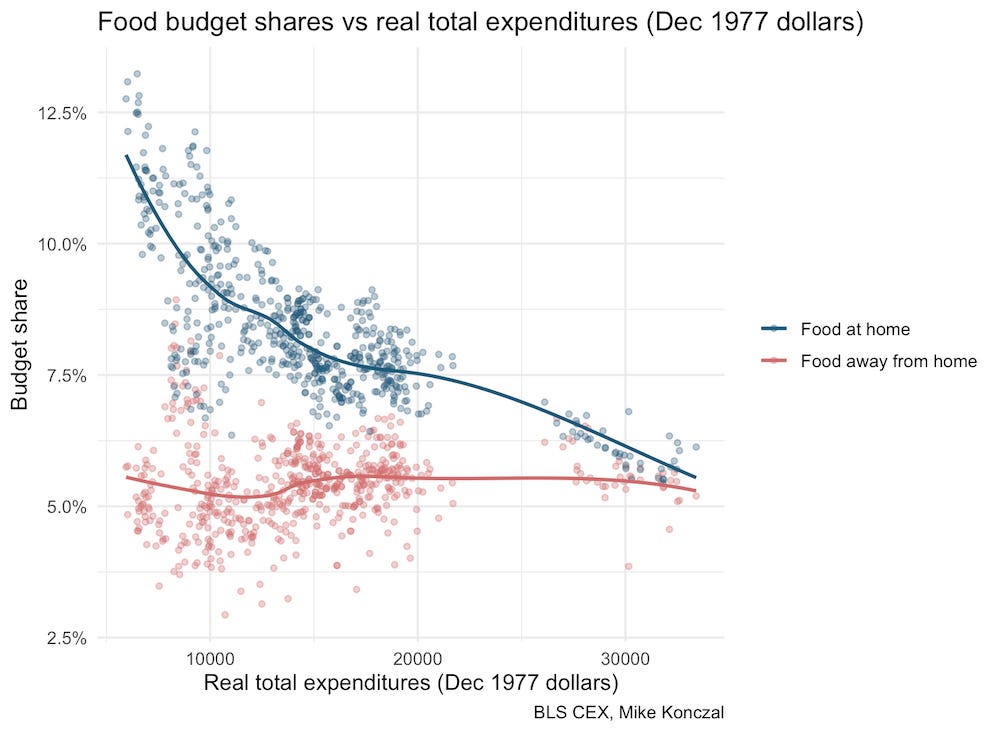

Second, the longer-run trend matters. Historically, as incomes rise, the share of spending devoted to food at home falls. You can see that above, which is the percent of the budget spent versus real total expenditures (the same is true for nominal) for each quintiles of each year from 1980 to 2024. There is a very strong decline in food at home as people get wealthier.4

That doesn’t just mean people dislike cooking. It means that, with more resources, people tend to allocate more toward convenience and variety. A lot has changed in preferences and attitudes these past seven years, but the fact that more of the budget has shifted to a good that declines with income should give us a strong presumption of disutility. The affordability crisis is real.

What About the Kids?

Ok, but can we still blame the kids?

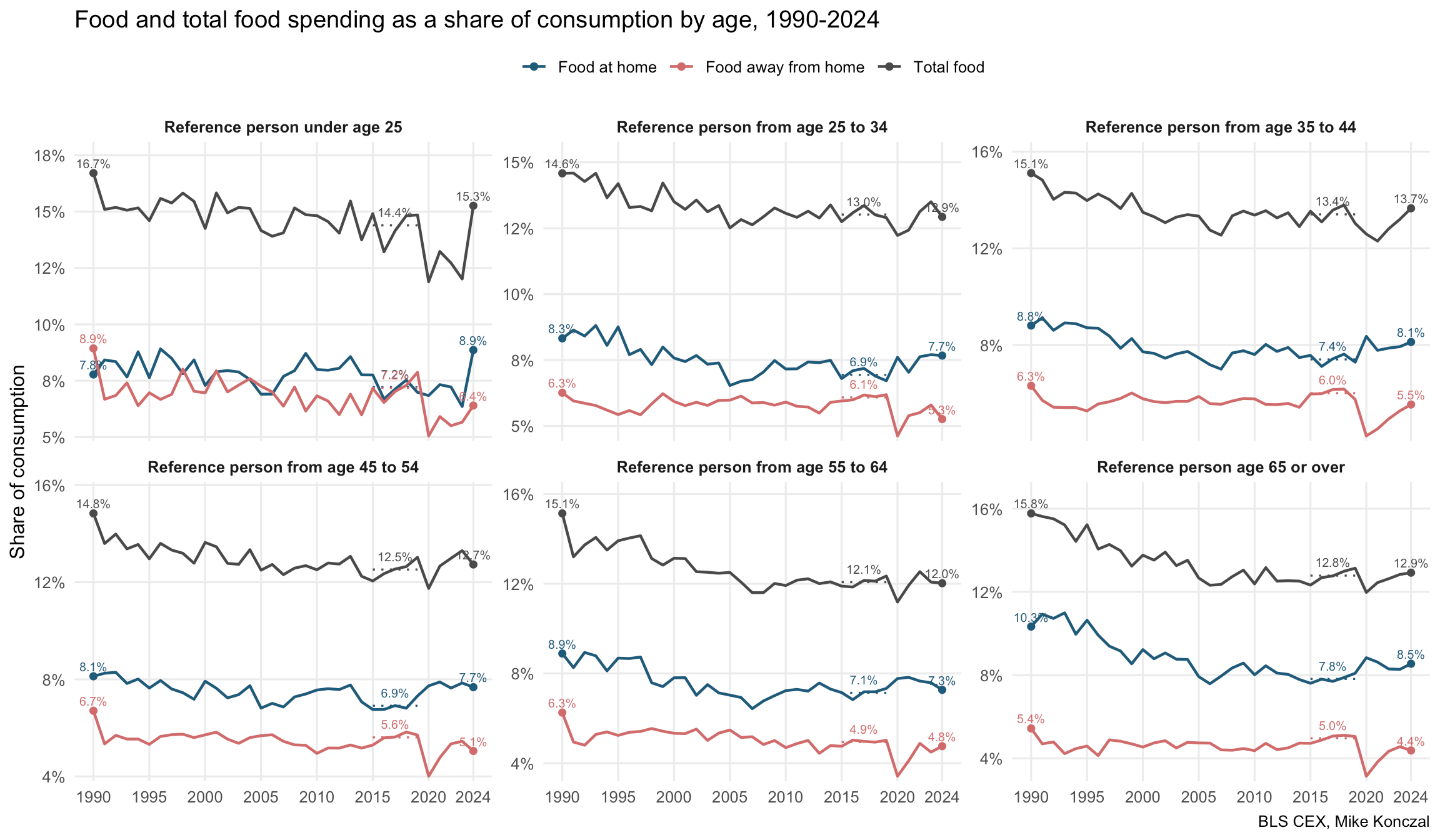

The same exact thing happens, with the pattern being most pronounced among people under 25. They experienced the largest shift toward food at home. The 1.7 percentage point shift toward cooking at home for those under 25 is 2.5 times larger than the 0.7 shift for the general population.

The kids are alright. They're just broke and cooking at home to make up for it.

Before you ask, and it is a good question, “food away from home” should include DoorDash. Here’s the BLS’s Consumer Expenditure Surveys glossary:

Food at home refers to the total expenditures for food at grocery stores (or other food stores) and food prepared by the consumer unit on trips. It excludes the purchase of nonfood items.

Food away from home includes all meals (breakfast and brunch, lunch, dinner and snacks and nonalcoholic beverages) including tips at fast food, take-out, delivery, concession stands, buffet and cafeteria, at full-service restaurants, and at vending machines and mobile vendors. Also included are board (including at school), meals as pay, special catered affairs, such as weddings, bar mitzvahs, and confirmations, school lunches, and meals away from home on trips.

These results are the same if you do item spending as a percentage of total income rather than total consumption. For low income quintiles, they are spending more than they earn, which can lead to some exaggerated data.

Code for graphics and analysis is here. Note downloading CEX flatfiles is part of my tidyusmacro package in GitHub, but not yet in CRAN. Still working on version 0.2!

I am not going to use this to drive a full Stone-Geary linear expenditure system in a blog post…unless any asks for it?

Well argued! COVID definitely changed our outlook. We were forced to give up restaurants, but then decided we didn’t miss them…the wait, the crappy service, the screwed up orders. Cooking wasn’t so bad once we got back in the groove. We mostly just eat out when we’re traveling, which is enough.

Good post! What's with that hole in the data between 20k and 25k? Just curious.