What Progressives Want to Know About Abundance

Off Twitter/X, the concerns are about boundaries, business, omnicauses, and what complements liberal priorities versus what replaces them.

This week I participated on a panel titled “Abundance and Social Democracy: Enemies or Allies?” as part of a day of private discussion about tensions within the Democratic Party.

This was organized before Senator Elizabeth Warren called out the Abundance movement in a speech about the party’s future, which kicked off fighting on X, as well as posts by Ben Winsor of the Open Markets-affiliated Liberty and Power Substack and Jonathan Chait of The Atlantic.

Given the interest in the topic, I thought I’d share the notes I prepared, written up after reflecting on the discussion.

On tensions between Abundance, as popularized by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book, and more populist approaches, I think this is mostly a solved problem as we enter 2026.

Democratic campaign veterans like James Carville and David Plouffe emphasize populist messaging focused on affordability and economic pain. Virginia Governor Abigail Spanberger and New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani each spent their first days announcing serious efforts to identify ways to streamline housing production. Spanberger launched her Commission on Unlocking Housing Production, and Mamdani created his LIFT and SPEED task forces. We are arriving at a synthesis that emphasizes both challenging high prices and bad actors while also prioritizing longer-term supply-side issues.

This isn’t surprising. Whether creating an effective new agency in the CFPB or rebooting an older one in the FTC, progressives care about how well the government works. There is also a long-standing streak of YIMBYism across parts of the left.1

But when it comes to rank-and-file progressives, there’s still a genuine confusion and discomfort with Abundance. This isn’t just a positioning fight within the Democratic Party. To keep things grounded, here are three specific questions that point to bigger issues.

1. “Does Abundance require the federal government to overrule state-level AI regulation?”

The Abundance Institute is one of the leading policy advocates calling for the federal government to block state-level AI regulations, a live issue during the tax bill debate and again recently with a potential executive order.

This led to funny moments where Abundance people were mad that someone might assume the Abundance Institute speaks for Abundance. The Institute had to clarify that they actually had the name first, years before the book. This created some genuine confusion: who exactly speaks to the boundaries of this movement?

If Abundance means YIMBYism, building more housing and preempting exclusionary local zoning, I am 100 percent a supporter and encourage people to contribute. If Abundance means e/acc, letting tech and AI rip across every domain regardless of consequences, I am not in favor and encourage people to be critical. When I encounter Abundance in Washington, D.C., I’m never sure which of these two I’m going to get. It takes time and cognitive work to figure out which is which, time most people don’t have.

A movement driven by magazine writers and academics will find it difficult to police the boundaries of what’s included and excluded. When the Center for American Progress writes convincingly against state AI preemption, we know how that stands institutionally. If an Abundance-affiliated writer argues against it, does that count for the movement? There are big stakes here: $150 million in AI lobbying is being deployed against elected officials, including on this basic preemption question. How should progressives understand what gets included and excluded?

2. “Does Abundance require endorsing charter schools?”

You can sometimes see Abundance thinkers say that the theory calls for charter schools. Setting aside your own views on charters, they are clearly a different matter than the YIMBYism policies Abundance has been associated with. But they do fit if Abundance is meant to be a centrist omnicause.

The omnicause is a term for the gravity well that pulls politics into ideological alignment. If you are progressive or conservative on one topic, you tend to end up the same on all topics. There are interpersonal, institutional, and technological (e.g. social media) reasons this happens. Right now you can read many Abundance authors and thinkers argue that the term should function as an omnicause for centrists.

This is how I understood Abundance in early 2024, well before the book came out. Abundance was pitched then as a self-conscious moderating “faction” within the Democratic Party. The surprise bestselling success of the book and the increased prominence of YIMBYism in Democratic electoral politics were in some ways a temporary detour away from this idea.

To avoid sounding conspiratorial, consider two prominent YIMBYs who are uncomfortable with this move. Editor-in-chief of The Argument Jerusalem Demsas writes: ‘Don’t make abundance the moderate omnicause.’ She worries that Abundance will get “watered down into a sort of umbrella term used by vaguely pro-business centrists who want a new slogan.” If this happens, Abundance will lose the more radical implications of YIMBYism (and the practical political anchor it provides) and instead become a buzzword for people who want to moderate the party.

And former policy director for California YIMBY, Ned Resnikoff, had a Roosevelt Institute paper, “Lessons from YIMBYism: Taking ‘Abundance’ Back to Its Fundamentals,” on how to apply YIMBY principles across economic topics. The piece starts with an important intervention about how Abundance has become so “ideologically capacious,” often “pursuing entirely different and mutually exclusive objectives” where it isn’t “possible to build a coherent synthesis that accommodates” them all. As a result, he’ll just stick with describing YIMBYism instead:

I use the term YIMBYism instead of abundance throughout to emphasize that this essay is about a particular policymaking approach, and not about the larger ideological debates that have become part of the abundance discourse.

I think Resnikoff has ended up at the correct place. YIMBYism has important insights across domains. The rest of Abundance, though, can feel like a confusing grab-bag of priorities.

3. “Are the Affordable Care Act and lowering prescription drug prices part of Abundance?”

A recurring move among some Abundance advocates (it’s in the book) is to characterize the Affordable Care Act as a pure demand subsidy, throwing money at coverage without any effort to manage supply or delivery.2 This is confusing. From creating the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, to implementing bundled payment initiatives, or launching the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program and the Medicare Shared Savings Program, the ACA spent enormous energy on healthcare delivery and “bending the cost curve.”

It’s the right of every writer to say their idea has never been tried before. But if more direct measures to bending the cost curve are written out of Abundance, where does this leave us? Take a voter worried about their kid seeing a doctor. Imagine a candidate responding that their main effort will be removing certificate of need requirements for new hospitals and taking on the AMA to expand residencies. And that’s it. How does that help this parent now? And how can they be certain it helps them later? Will new hospitals actually get built? Will insurers pass along that supply as actual access? Will it translate into care?

These are good ideas, but supply-side reforms work on long timelines, and the benefits and their distribution are uncertain. The causal chains are long, and voters are right to be skeptical of politicians promising that they will automatically do things and help. And as Bharat Ramamurti notes, without some measure to directly address people where they are, it is difficult to pass these supply-side reforms.

The Affordable Care Act, whatever its limitations, got over 20 million people coverage while reducing projected healthcare spending by hundreds of billions of dollars relative to baseline. This looks like Abundance to me: better outcomes at lower prices by reducing unnecessary spending and harnessing the government’s capacity to operate at scale. If the ACA gets read out of the Abundance framework, what should progressives, who want to expand Medicare and create public options, make of the agenda?

The book itself seems conflicted on drug prices. Klein and Thompson note that European countries achieve lower costs because their governments negotiate prices, versus our “hodgepodge of private and public insurers who do not coordinate and do not effectively negotiate,” which they characterize as weak “state capacity.” But they don’t follow through on this logic. And the broader Abundance conversation is even more muddled. I’ve spoken with people adjacent to this world who suggest that real Abundance means abandoning the prescription drug price controls in the Inflation Reduction Act, with the Democrats deprioritizing lowering drug prices through negotiation because of the risk to pharmaceutical innovation.

If Abundance is a supply-side complement to traditional liberal priorities like healthcare, then that’s valuable. But it can come across as if it’s meant to displace or subordinate those priorities instead.

It’s not surprising that progressives are confused by what Abundance is offering. If it’s YIMBYism plus supply-side complements to traditional liberal goals, that’s a coalition worth building. If it’s a centrist omnicause that wants to replace liberal priorities with smaller goals unlikely to win politically or deliver substantively, and whose only checks against business capture are writers otherwise busy getting people to click, like, and subscribe, progressives are right to be skeptical it’s a good direction to go.

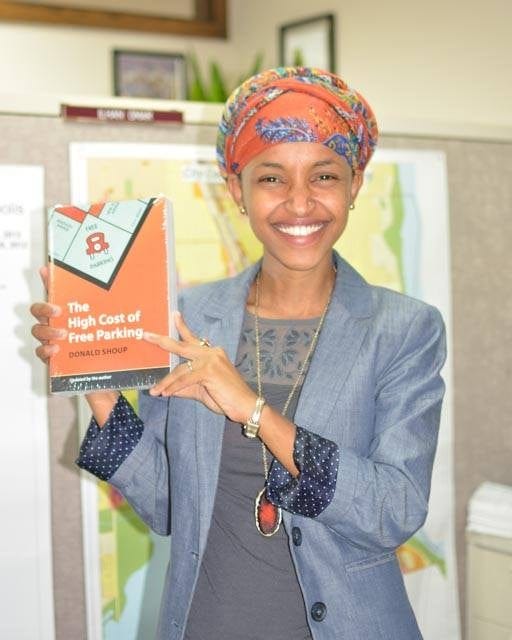

Back in 2012 I had the editors of Parking Today red-baiting me, “Shoupista or Sandinista?”, for discussing dynamic parking pricing from a progressive perspective.

I do find it funny during the Abundance ascendance the Searchlight Institute found that “allowing housing to be built without parking spaces,” which is table stakes for being a YIMBY, is the most unpopular message on housing they polled at -46%. It may be the most unpopular message on their website? For contrast, “Abolish Ice” is at -6% in polling Searchlight highlights.

“Progressivism’s promises and policies, for decades, were built around giving people money, or money-like vouchers, to go out and buy something that the market was producing but that the poor could not afford. The Affordable Care Act subsidizes insurance that people can use to pay for health care. […] These are important policies, and we support them. But while Democrats focused on giving consumers money to buy what they needed, they paid less attention to the supply of the goods and services they wanted everyone to have. Countless taxpayer dollars were spent on health insurance […] without an equally energetic focus—sometimes without any focus at all—on what all that money was actually buying and building.” - Abundance, page 7.

“The Affordable Care Act was, to a first approximation, just an insurance expansion. It left many opportunities to try to deal with high healthcare prices on the table. […] So you’ve got very high prices, and the Affordable Care Act, to a first approximation, doesn’t address them at all. Instead, what it does is subsidize demand. By bringing more people into the insurance system, it basically adds fuel to that fire […] it left undone the project of trying to get a handle on high healthcare prices.” - Nick Bagley, to Briefing Book.

Don’t mind me as I share this piece with every friend and family member who was skeptical about Klein and Thompson’s book!!

Well done Mike. Thanks!