Mass Deportation Will Save Renters Less Than $5 a Month

President Trump wants to deport his way to affordability. But immigration can’t explain the housing crisis, and deportation won’t fix it.

Housing is a major affordability concern for Americans, and the Trump administration has a plan to address it: deportations. As Vice President J.D. Vance said to Fox News:

“A lot of young people are saying, ‘Housing is way too expensive.’ Why is that? Because we flooded the country with 30 million illegal immigrants who were taking houses that ought by right go to American citizens.”

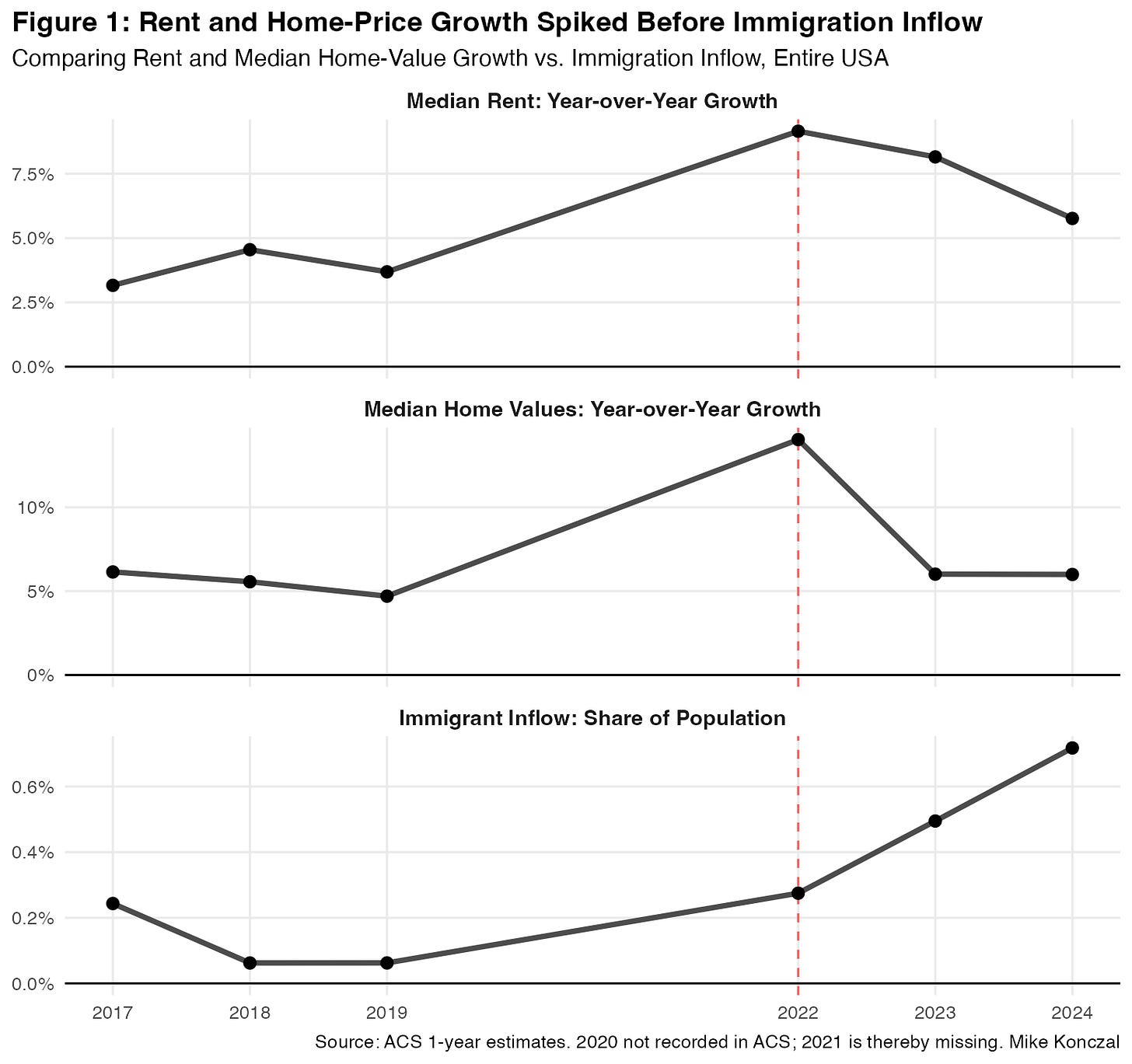

That claim is incorrect. The ‘30 million’ number is wrong. But beyond that, as Figure 1 shows, the rate of rent and home value increases peaked in 2022, along with the rest of inflation, and slowed from 2023 to 2024 even as immigration accelerated.

But maybe deportations could still make a difference and help renters. How much would mass deportation lower your rent? The Trump administration relies on a specific 2007 study, a standard in the field, “Immigration and housing rents in American cities,” by economist Albert Saiz. The Trump team points to it, and the Trump White House official on the Federal Reserve’s FOMC, Stephen Miran, cited it in his first Fed speech.

Saiz (2007) finds “An immigration inflow equal to 1% of a city’s population is associated with increases in average rents and housing values of about 1%.” Note what’s in the denominator of this elasticity: it’s the initial total population, not just the number of immigrants.

This gives us what we need to run the numbers. Let’s say there are 342 million people in the U.S., and the average rent is $1,500. Let’s define mass deportation as the government putting into motion an operation that results in 1 million immigrants leaving. Using the Saiz (2007) estimate, we get:

If they pulled this off, renters would save roughly $4.39 per month. To put that in context, economists have estimated the cost of RealPage’s AI algorithms using anticompetitive practices to determine your rent is around $70 a month. $4.39 is not going to make a meaningful difference, or really any noticeable difference, in the rent people face. And there are multiple issues here.

Beyond the Initial Estimate

Note that the Saiz estimate isn’t a low one across the literature. Ottaviano and Peri (2012) find an elasticity of 0.6 to 0.82 overall, though it can vary up to 2.3 depending on skill. Sharpe (2019) finds a much lower value of 0.3 to 0.4.

Let’s take a moment to understand why this is a difficult thing to measure. The intuition seems simple: immigrants move to an area, increasing housing demand. Since housing supply is fixed in the very short term, prices go up. But immigrants don’t move to random zip codes. They move to booming cities where jobs are plentiful and wages are rising. Those cities were already seeing rents go up because of that economic heat. Separating “rent growth caused by immigrants” from “rent growth caused by a booming economy that attracted immigrants” is the challenge of the literature. That’s why estimates differ. Even so, the range of estimates is not large enough to generate meaningful savings for people.

Maybe there was a break in this recent period? I don’t believe so. I downloaded Census 1-year ACS data on median gross rent, both foreign-born and overall population, and median household income, for all core-based statistical areas (the standard in the literature). This is quick-and-dirty. I’m not going to try to control for the reverse-causation issue here as I want to see if there’s a break in the estimate, and, since immigrants tend to move to booming cities where prices are already rising, I assume the reverse-causation biases upward making this a ceiling estimate.

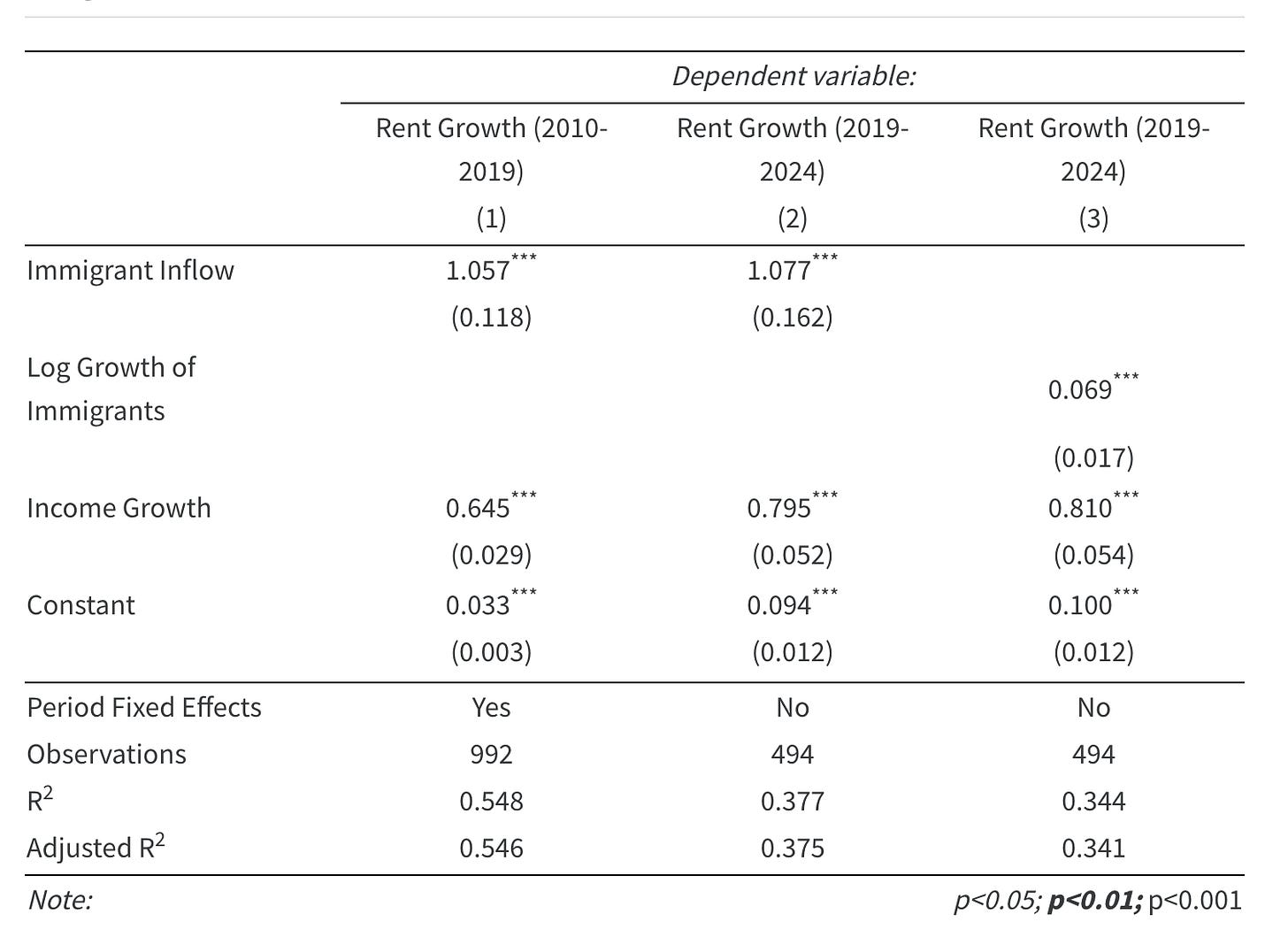

Code, including to download the data from Census, is here; modeling choice details in the footnotes.1 Model 1 finds the standard result that, controlling for income, a 1% increase in immigrants correlates with a 1% increase in rents for 2010-2019. Model 2 finds the same number for 2019-2024. This is a quick glance, but I’m not seeing any kind of break that would cause this number to have skyrocketed in the post-pandemic period. Note that in 2019-2024, both the constant and the effect of incomes increase.

I want to make sure that this denominator issue really matters. Model 3 uses the (log) percent increase in immigration rather than increase divided by total population. Immigration is still significant but is now a much lower value, which makes sense because it’s a much smaller denominator. This reminds us that it is important to check how people describe the value: if anyone differs from total population in the denominator we know that’s off.

Though it’s a heated debate, I haven’t seen this mistake in the broader discourse. With one exception. Stephen Miran, in his first FOMC speech, says:

”Work by Albert Saiz finds an elasticity of rents with respect to the number of renters of about 1, identified from a large quasi-random immigration shock. Net immigration averaged roughly 1 million per year in the decade leading up to the pandemic. Given that roughly 100 million Americans rent, net zero immigration going forward would imply 1 point lower rent inflation per year.”

I was going to leave figuring out the error here as an exercise to the reader but, as ChatGPT 5.1 pointed out to me while fact-checking this post, the study author was forced to jump into this. Imagine being Saiz himself and having to explain to reporters that someone sitting on the Fed messed up this elasticity question from research you published eighteen years earlier.2 Here’s Saiz speaking with Ann Saphir from Reuters, confirming our analysis above (my bold). Reuters:

Miran, in his debut speech as the Fed’s newest policymaker, latched onto that idea but didn’t follow Saiz’s formula - choosing an estimate of the national renter population of about 100 million people as his denominator rather than the far-larger total U.S. population of 340 million. The result was an imputed impact on inflation about three times larger than using Saiz’s approach.

“If you did the calculation using the right magnitudes, you get 1 divided by 340 million - that’s about 0.29 percent a year,” Saiz said in an interview. Given that the share of housing in the consumer price index is about one third, the overall impact on consumer inflation would be at most 0.1 percentage points, he said. “Obviously population growth does impact the price of housing, but the magnitude isn’t big enough to justify major changes in monetary policy.”

Additional

But there’s more. Three additional notes:

This administration is unlikely to reduce the immigrant population by 1 million people. There’s an interesting debate on how much of the 2025 immigration slowdown is due to Trump’s immigration actions, rather than steps taken in 2024 and Trump’s collapsing labor market in 2025. But the overall immigration level is unlikely to drop.

Over time, supply adjusts. But the loss of workers is immediate. Deporting people means losing construction crews, plumbers, and maintenance staff, which directly constrains housing supply. If the price of construction increases, it’ll more than offset these nonexistent savings for renters. Worse, reporting suggests deportation quotas are being met by diverting federal agents away from serious criminal investigations, creating social costs that go far beyond housing. So the more you try to scale up deportations, the bigger the longer-term costs to everyone.

Saiz (2007) and other papers study immigration as a whole. But it’s also understood in the field that the undocumented population is different from the rest of immigrants. They are more geographically concentrated: Pew Research Center finds that “In 2023, the top six states were home to 56% of the nation’s unauthorized immigrants.” And they may put less pressure on rental markets, since they have less access to the formal legal and credit systems for renting. Huang, Li, and Xu (2025) find no state-level relationship between unauthorized immigrants and rental prices.

Immigration isn’t the reason housing is expensive. We have a strong empirical consensus on what drove skyrocketing rental and housing-price increases in 2021-2022. As Riordan Frost summarized, demand was propelled by pent-up household formation among native-born millennials, pandemic-era demand for more housing and larger homes (especially for remote work), historically low mortgage rates, and it ran straight into inadequate and sluggish supply. We have enough stories about what caused a rise in rents, without needing claims that do not hold up to basic scrutiny.

I construct the 2010s as 2010-2014 and 2014-2019, to mirror the 5-year difference of 2024-2019 without going into the 2000s. I use longer time differences rather than annual ones because I rely on Census rents, which update less frequently. I do not attempt to substitute in current market rents from other sources. Immigrant inflow is the change in immigration divided by area total population in the previous period. Income and rent growth are in logs. Rent is gross rent, which includes utilities. I use population total as weights because I don’t want city-level elasticities per se, but instead the total cost to people across the country, as this is a policy choice we are debating.

This is a good justification for picking whether you are the chair of the CEA or a FOMC member. Trying to do these two full-time jobs at once will ensure you mess up basic units of elasticity questions.

Going beyond alternative facts to alternative math ....