Does a Target Range Make Sense of the Fed's Actions?

Why the Fed may be acting as if inflation has a band, not a point. And why bands are good!

A lot of people are confused about where the Federal Reserve is right now: cutting rates even as it acknowledges that inflation is picking back up. It’s not an easy situation, as their statement notes: “Inflation has moved up since earlier in the year [and] downside risks to employment rose in recent months.”

Much of the coverage has focused on how divided the Fed appears. Joe Weisenthal had a column noting it is as if “that implicitly the Fed has already abandoned its target” and Matthew Klein wonders if the Fed has submitted to political demands.

A Target Range

Here’s a theory of what the Fed is thinking. I’m not entirely sure whether this reflects what Fed officials actually believe, a useful way to model how they behave, or simply what I think they should be doing. It’s just a take.

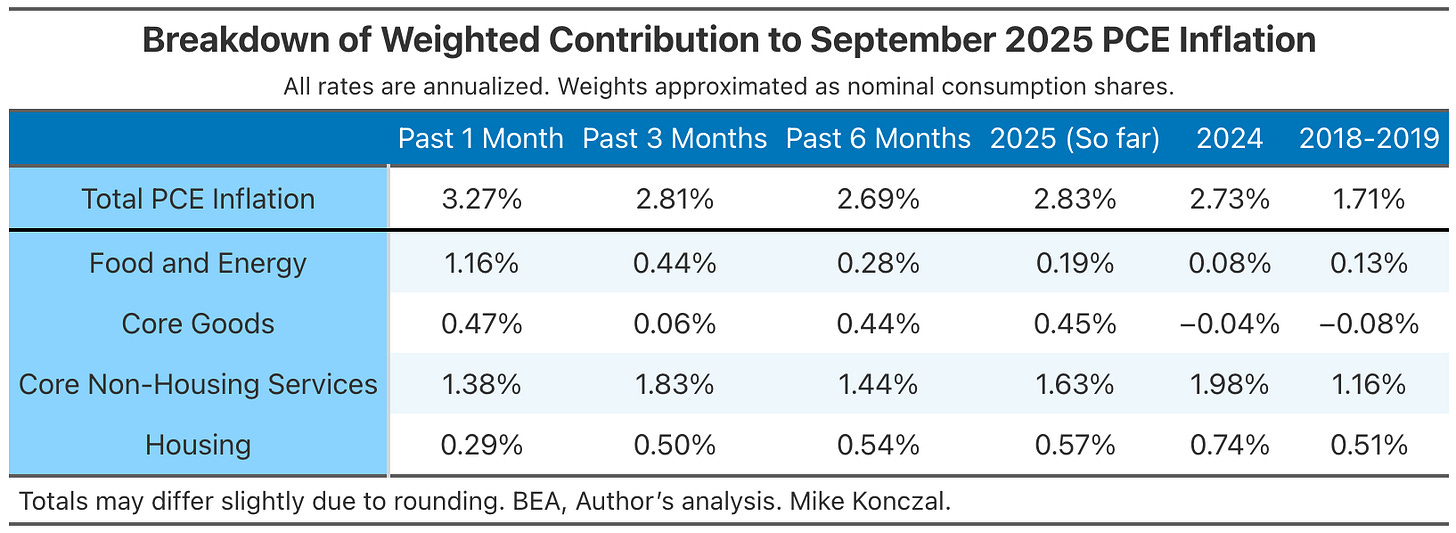

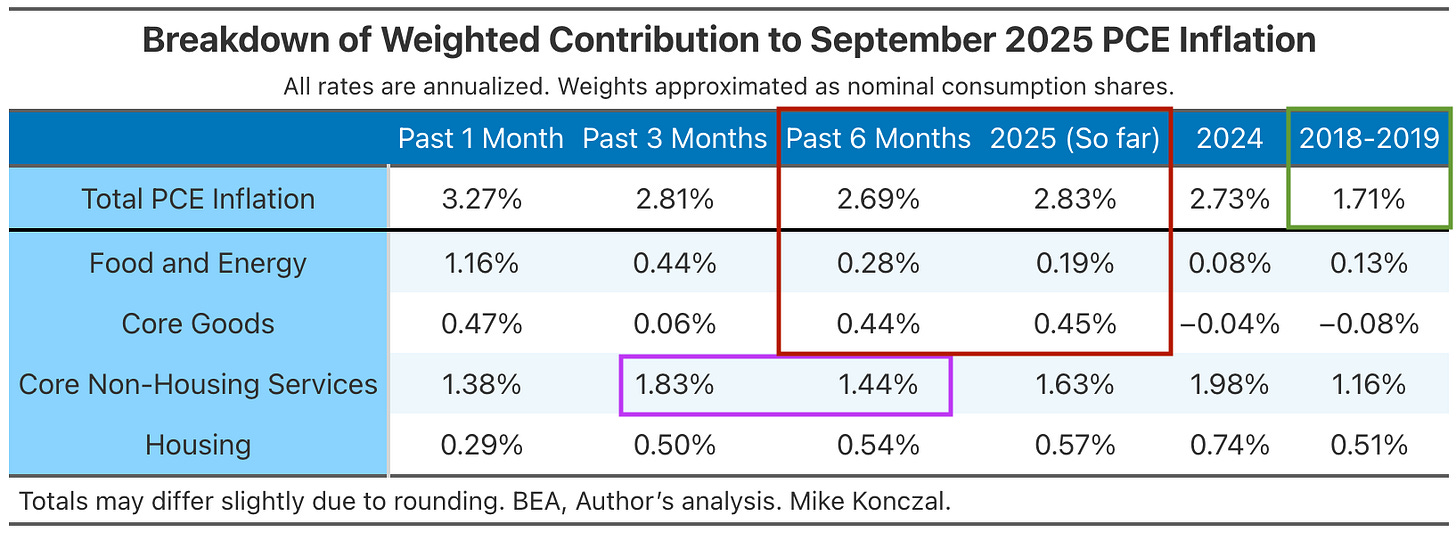

My theory is that the Federal Reserve acts as if they have a target range of between 1.6 and 2.4 for inflation, and their dovishness and hawkishness alternate as they get to either end of the range. Why is that? Here’s a chart I watch closely on PCE inflation:

And here it is marked up to follow a few points:

This is total PCE inflation, what the Fed targets at 2 percent, along with four contributors that account for the total. Start at the upper-right green-colored box. Across 2018 to 2019, inflation was 1.7% a year. When inflation was much lower earlier in the 2010s, they did a lot to try and boost economic activity, including Operation Twist and Quantitative Easing (QE). But when inflation was 1.7% they did not stress much about it being too low. They instead defaulted to having a dovish lens on events as they happen, such as letting unemployment drift into a rate below 4 percent alongside strong real wage growth, while giving speeches on how unknowable r* is.

Let’s jump forward to now, and discuss the red-colored box. Over the six months prior to September, inflation was 2.7%. Yet 0.44% of that is in core goods, which was zero in 2024 and zero in 2018-2019, and is largely attributable to the one-time impact of Trump’s tariffs. That puts underlying inflation right at 2.26%. 2.26% is not 2.0%. But 2.26% is not something you should cause a recession to end.

However, being at the top-end of the range does put a hawkish lens on new events as they happen, mirroring the dovish lens on being at the low-end in 2018-2019. So when the tariffs, for instance, show up, the Fed is rightfully concerned about them breaking expectations, or becoming more persistent, or also causing a shift in services to bring their respective price levels into balance. It’s too close to the upper-bound of the range to assume it’ll act like a tax and nothing else, because if something breaks here you are well outside the range. You’ll keep more of the headline inflation rate in your Taylor Rule calculations.

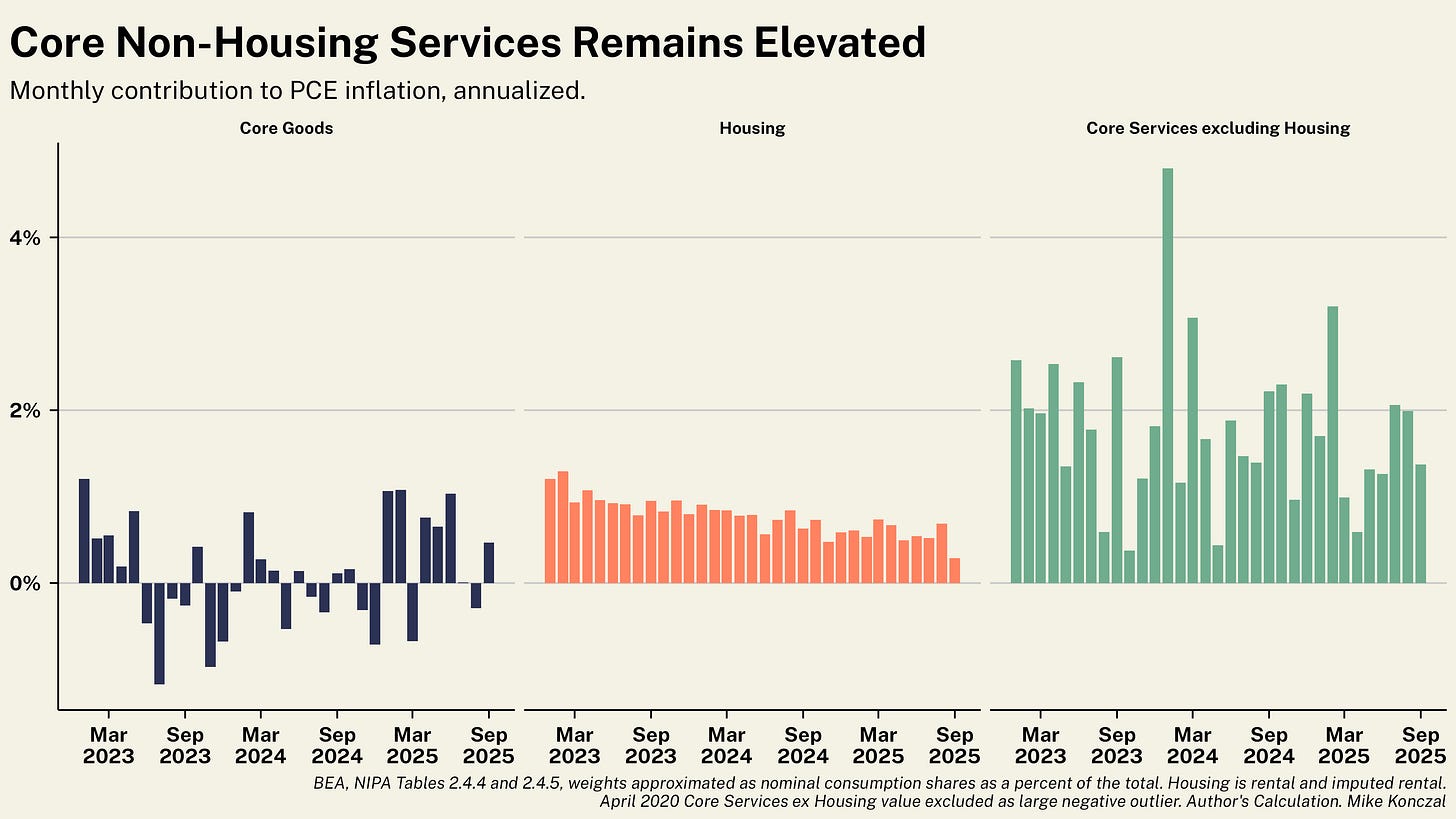

So what about this divisive vote? One implication of operating near the top end of an implicit range is that it creates sharp discontinuities in how different policymakers read the same data. A slightly different read puts you either inside or outside the range. Take the purple-colored box in the chart above, where over the past three months inflation is still in the ~2.8% range, but now it’s all in services, not goods. You can see this in the chart below. Normally you wouldn’t over-index on any three-month period. But we’re at the top-end of the range, making us more nervous about these short-term movements, so that’s why many want to hold.

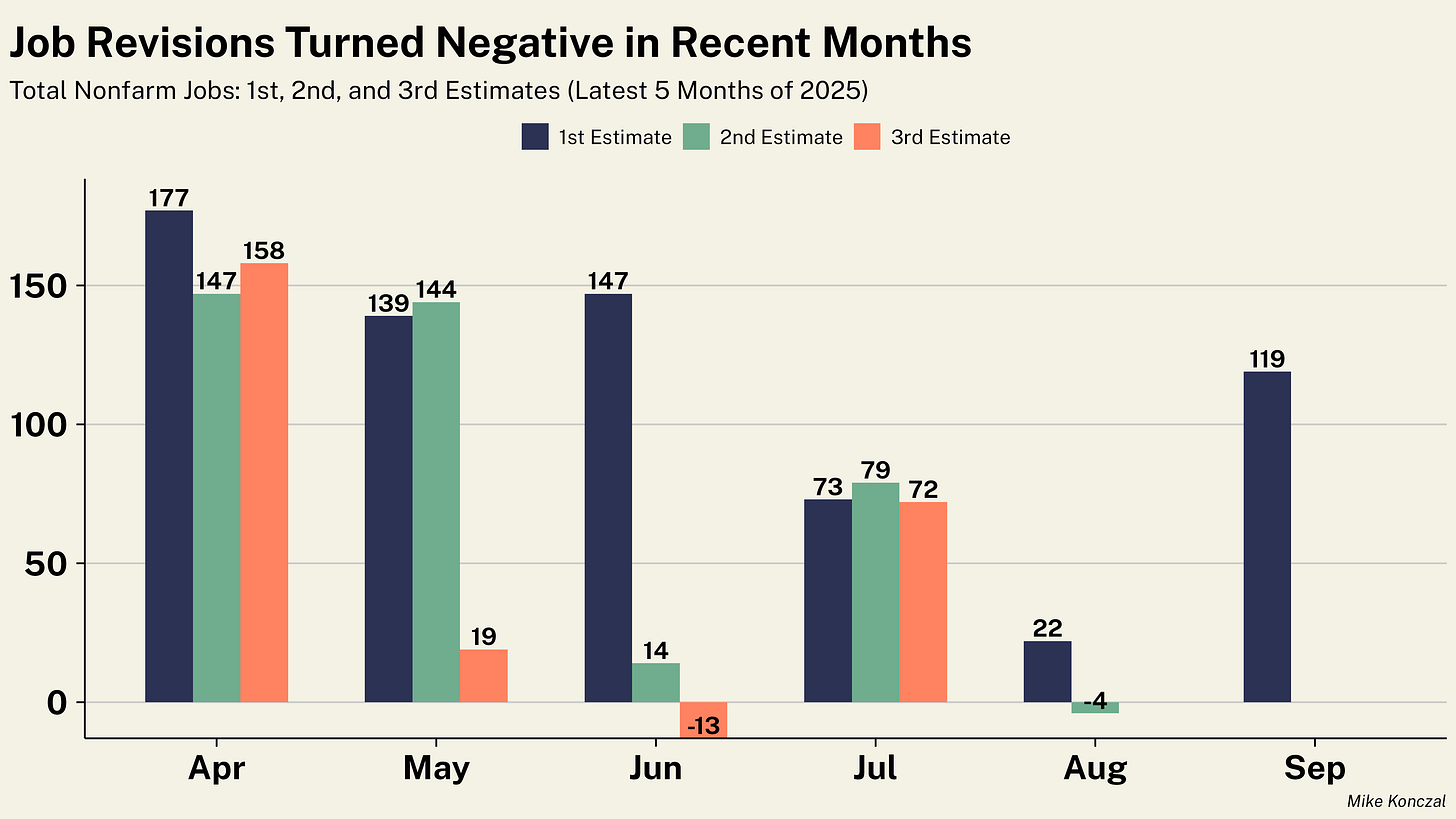

Yet, we’ve also seen the labor market weaken in the last several months, with, as you can see below, negative job growth in two out of the last four months. Other labor market measures are going south. It’s unclear whether this is because demand is falling or potential is, because of deportations and tariffs.

Meanwhile there’s a third way to read the data. Some still work for the White House but are on leave, and others are aiming to get Powell’s job next year, pushing them in the more dovish direction in reading the data.

Ranges are Good

The macroeconomist Greg Mankiw had a good argument in 2024 that “A target of 2 for inflation is better than a target of 2.0.” From the piece:

I feel strongly that a target of 2 percent is superior to a target of 2.0 percent. The difference between these targets, of course, is the number of significant digits. If you recall some science class you had in high school, you likely learned that the number of digits a person reports should reflect the precision of his or her estimate. Central bankers often forget that lesson. They sometimes speak as if they are targeting an inflation rate of 2.000 percent.

It would be better if central bankers admitted to the public how imprecise their ability to control inflation is. They should not be concerned if the inflation rate falls to 1.6. That comfortably rounds up to 2. And they should be ready to declare victory in fighting inflation when the inflation rate gets back to 2.5. As the adage goes, that is good enough for government work.

Maybe the Fed should even ditch a specific numerical target for inflation and instead offer a range. It could say, for example, that it wants to keep the inflation rate between 1 and 3. Doing so would admit that central bankers are not quite as godlike as they sometimes feign.

I like ranges. Back at Team Macro at the Roosevelt Institute, the economist Justin Bloesch put out an excellent paper with the case for an inflation range of 2 to 3.5 percent. Explicit inflation ranges are used by Canada (“The Bank of Canada aims to keep inflation at the 2 per cent midpoint of an inflation-control target range of 1 to 3 per cent”) and Australia (“Australia’s inflation target is to keep annual consumer price inflation between 2 and 3 per cent”), early adopters of inflation targeting that are widely viewed as having strong macroeconomic track records. Ranges also help resolve some of the persistent “catch-up” questions that complicate strict point targets. It’s good that the Fed might be using it, at least in my imagination.